The Social Equity Heist: Disparity Is a Feature, Not a Bug

Strict enforcement for the little guy. Loopholes for the powerful. Missouri removed the same bad actors that Arizona’s leaders allow to operate unchecked.

In this report, we examine how Arizona regulators stripped a young worker of a basic permit to serve cannabis behind the counter, yet allowed a well-connected owner with a felony record and 22 licenses revoked in Missouri to keep his lucrative Arizona licenses in violation of state rules. While Missouri has aggressively cracked down on the same kind of unethical license usurping, Arizona’s Social Equity Ownership Program has been left wide open to abuse, with the Hobbs administration reportedly killing corrective legislation and Attorney General Kris Mayes refusing to investigate, effectively turning a blind eye to corruption.

But first, a quick history lesson for readers unfamiliar with Arizona’s marijuana laws.

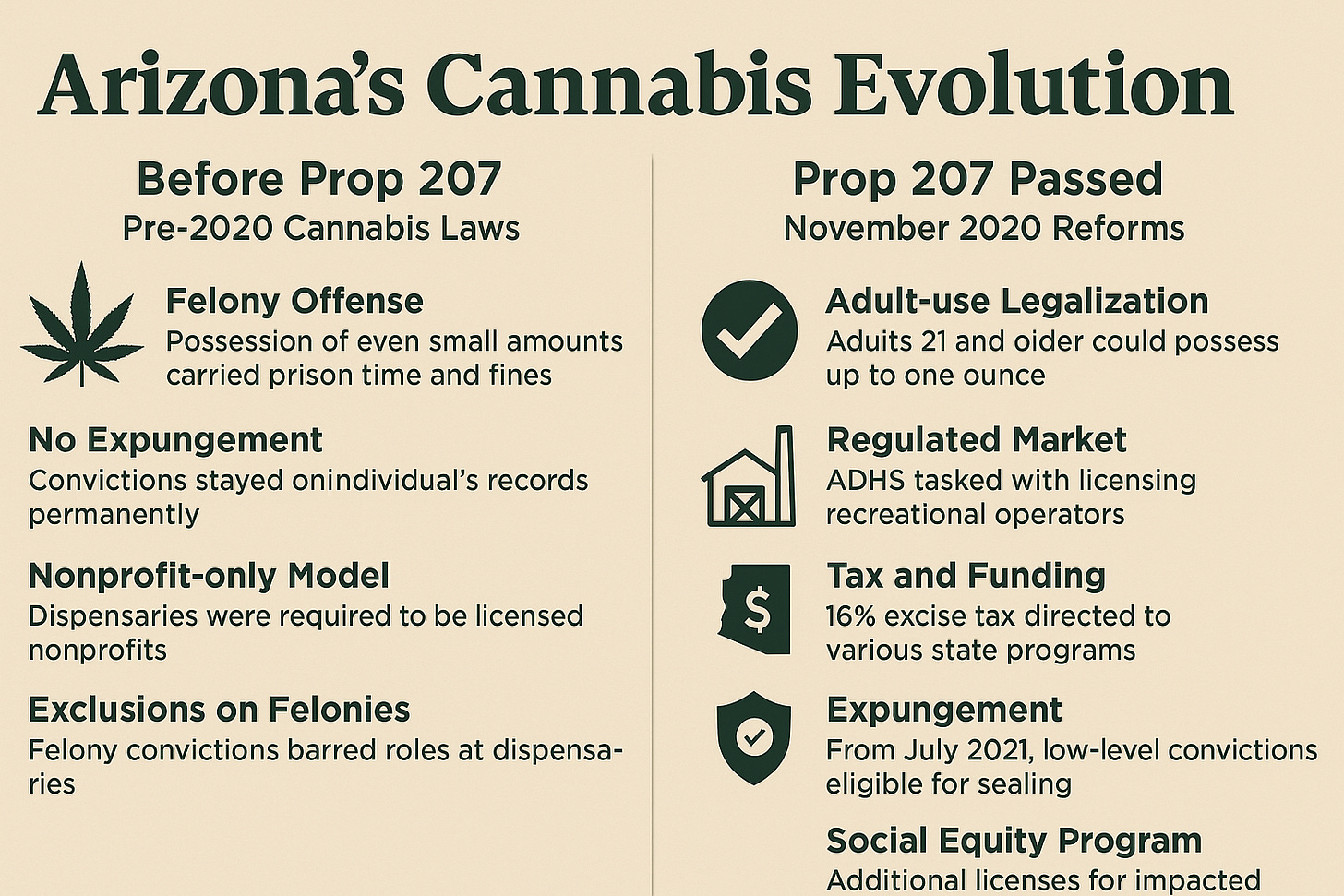

In just a decade, Arizona’s stance on cannabis has transformed dramatically, shifting from aggressive criminalization to controlled legalization. Critics say cannabis legalization made millionaires, but poor communities were left empty-handed.

Proposition 207, the “Smart and Safe Arizona Act,” passed in 2020 and ended marijuana prohibition by creating a regulated cannabis market. But it only squeaked through on the back of promises to poor communities.

Progressive leaders made it clear: without equity for disaffected minorities, they wouldn’t lend their support.

We previously reported that Chad Campbell, now serving as Governor Katie Hobbs’ chief of staff, chaired the Smart and Safe Arizona campaign and pledged “DEI-style” equity for predominantly black and Latino communities. The mission failed and effectively Campbell, Hobbs and Mayes have ignored the heist in the social equity program. If you missed that report you can find it here.

Beyond legalization, who was actually allowed to participate in the cannabis industry has always been marked by disparity. Access consistently favored those with money, legal expertise, and political connections, while communities most harmed by prohibition were locked out.

Before voters approved Prop 207 in 2020, Arizona had some of the harshest marijuana laws in the nation. Even small amounts meant a felony under A.R.S. § 13-3405, with no path to expungement. A narrow 2010 medical marijuana law offered limited relief but came with strict nonprofit rules, felony bans, and licensing barriers that shut out most small operators—especially in communities hit hardest by the drug war.

Prop 207 changed the law dramatically but it was flawed from the beginning. Adults 21 and older could now legally possess and grow cannabis, recreational sales launched under ADHS oversight, and a 16% excise tax began flowing into colleges, roads, and public safety. For the first time, people with low-level convictions could petition to clear their records.

But the initiative’s centerpiece was the Social Equity Ownership Program—licenses specifically promised to communities disproportionately harmed by past marijuana enforcement. It was billed as a chance to turn decades of punishment into opportunity. Instead, it has become the flashpoint for allegations of fraud, predatory contracts, and state inaction.

Photo Credit: GROK

Though Prop 207 was promised to broaden access, it has been dubbed a “DEI SCAM” - State 48 News covered this in detail in our previous report.

Existing medical dispensaries were first in line for recreational licenses—making it difficult for newcomers to compete. Social equity licenses were created to level the field, but applicants faced the same regulatory hurdles as others, including disqualification for certain felony convictions.

In the end, well-funded corporations partnered with social equity applicants through dubious means, raising concerns that the program functioned more as a diversity checkbox than a meaningful pathway to inclusion.

A state Senate special committee investigation revealed that most social equity license winners in Arizona may have been subject to predatory tactics by investors. Despite the law’s goal of economic justice, the program allowed corporations to co-opt social equity licenses, diluting their impact as reforms and prompting the label the “DEI scam”.

Disparate Treatment: A Tale of Two Owners

Arizona law strictly limits who may serve as an owner, manager or worker of a cannabis business. Both the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act (2010) and the Smart and Safe Arizona Act (2020) bar individuals with an “excluded felony offense” from having access to the industry.

That term is defined as either “a violent crime as defined in section 13-901.03(B)”—covering offenses such as murder, manslaughter, aggravated assault, sexual assault, and robbery—or “a violation of a state or federal controlled substance law that was classified as a felony in the jurisdiction where the person was convicted,” unless the violation involved only possession or use and occurred more than ten years before the application (A.R.S. § 36-2801(7); § 36-2850(10)).

In practice, this means violent crimes are permanent disqualification, while certain nonviolent drug felonies may be excused if a decade has passed or the conviction has been expunged under A.R.S. § 36-2862.

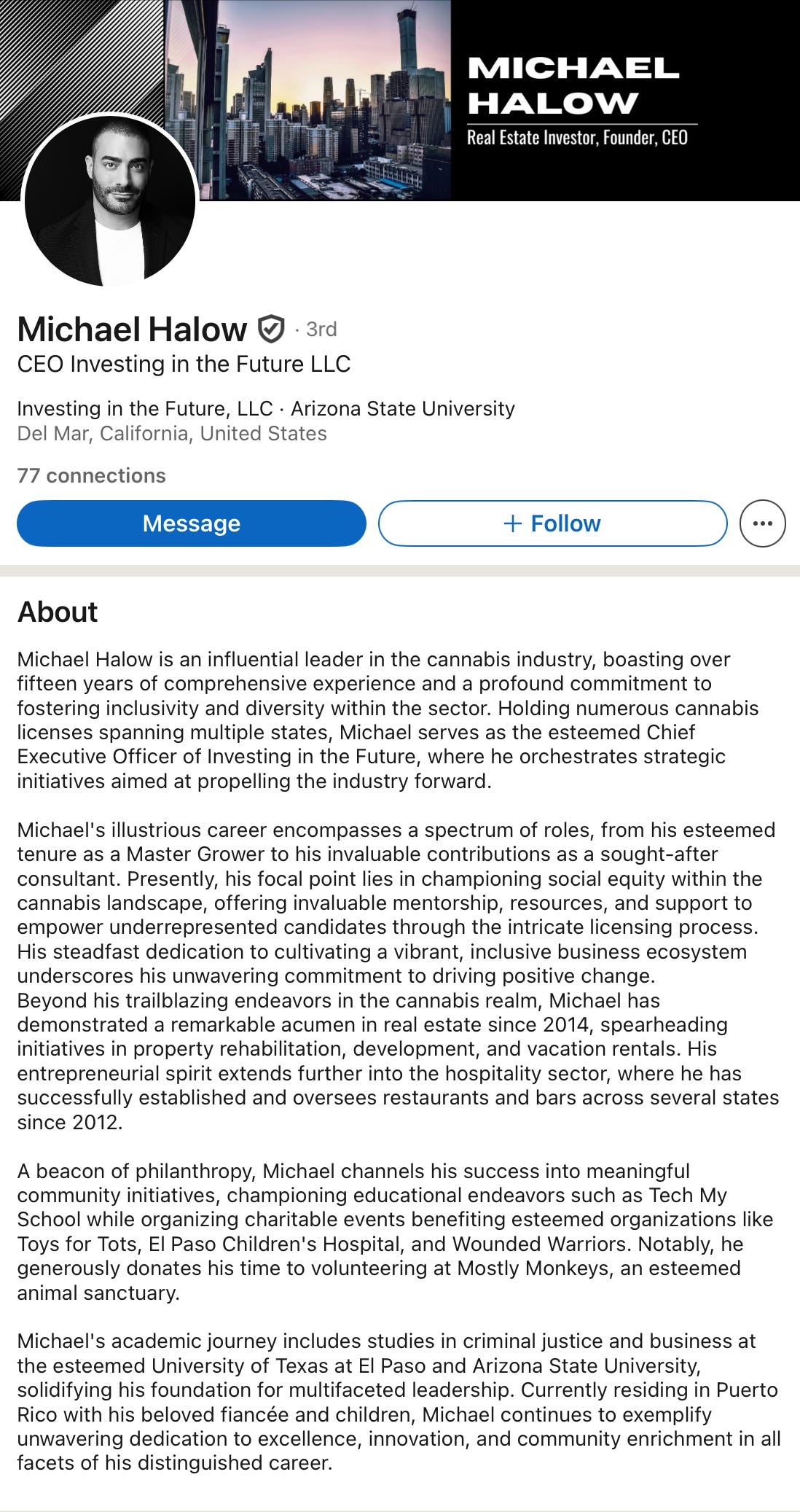

The Case of Michael Halow

In 2004, Michael Halow plead guilty in El Paso, Texas, to aggravated assault causing serious bodily injury (a second-degree felony) and received three years of community supervision; multiple 2003 charges—including counts of sexual assault of a child and producing child pornography, were dismissed under the plea, and after he completed supervision the remaining charges were formally dismissed.

Under Arizona law, a “violent crime” includes any criminal act causing death or physical injury or involving a deadly weapon (A.R.S. § 13-901.03(B)), and both Arizona’s medical and 2020 frameworks bar individuals with an “excluded felony offense” from serving as cannabis owners or agents.

Halow nevertheless became active in Arizona’s cannabis industry. Legal experts claim that his aggravated assault should permanently exclude him from the industry under Arizona’s laws.

Halow’s public profile states he lives in Puerto Rico and “holds numerous cannabis licenses spanning multiple states,” positioning himself as a mentor to equity applicants. The state of Arizona is continuing to allow an out of state corporate actor to allegedly scam legitimate social equity holders out of their licensees without consequence.

Photo Credit: LinkedIn

Halow has been linked to control of at least five Arizona licenses. Why has Arizona allowed a corporate, well-connected businessman with an adjudicated violent crime to remain a license holder? Courts have enforced his contracts, allowing him to retain influence even though, on the face of the statute, experts claim he is legally barred.

Halow has a pattern of social equity holders claiming that he fraudulently coerced them out of their licensees. In 2021, Phoenix residents Anavel Vasquez and Rene Mendoza were recruited via a “Planted Cannabis” postcard listing Halow’s name; the outreach tactic and mailers are documented across several states.

Arizona’s social-equity application fee was $4,000, which third-party investors often agreed to cover. Vasquez’s application drew one of the 26 social-equity licenses in the April 8, 2022 ADHS lottery; she later alleged Halow used contracts to seize control of her business.

In 2024, a Maricopa County Superior Court ruling declined to void or reassign the permit and left the license in Halow’s control and awarded him thousands in attorneys fees.

Arizona law requires that any cannabis license applicant disclose prior out-of-state license revocations. Under A.A.C. R9-18-303(A)(1)(e)(iv), applicants must attest that no principal officer or board member has “had an ownership interest in a licensed marijuana business that had the license revoked in another state.”

Similarly, R9-18-308(A)(7)(b) mandates establishments to ensure none of their principals “had or has an ownership interest in a licensed marijuana business that had the license revoked in another state.”

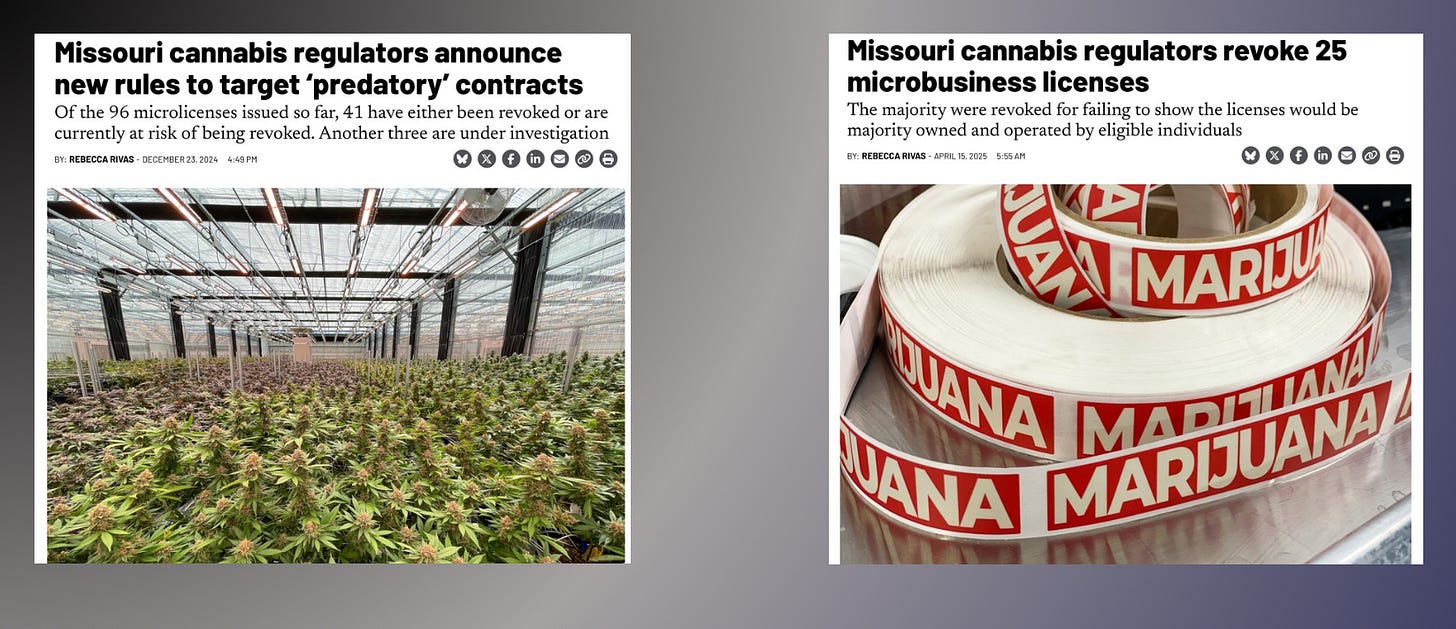

In Missouri, enforcement has become far more aggressive. Regulators recently revoked 25 microbusiness licenses in one sweep, bringing the total to 34 revoked out of just 96 issued, after confirming ownership had shifted away from eligible applicants. (Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services), (MJBizDaily)

Conspicuously, Mike Halow is connected to 22 of those revoked licenses, which represent the lion’s share of enforcement actions related to predatory contracts and opaque ownership arrangements. (Missouri Independent), (Marijuana Moment)

Photo Credit: Missouri Independent

Meanwhile, in Arizona, the story remains starkly different. Although laws clearly prohibit individuals with disqualifying convictions, or whose agents have out-of-state revocations, from maintaining control. Halow continues to be linked to multiple active Arizona licenses. Courts have upheld his contractual arrangements that effectively give him control behind the scenes—even though, on paper, his criminal history should bar him.

Missouri regulators are responding legislatively. New draft rules would empower them to prohibit previously flagged operators from obtaining new licenses, and require ownership arrangements to allow the removal of non-compliant parties.

Arizona, meanwhile, has done nothing, leaving enforcement loopholes untouched. The contrast is glaring, and the silence from Arizona leaders speaks volumes.

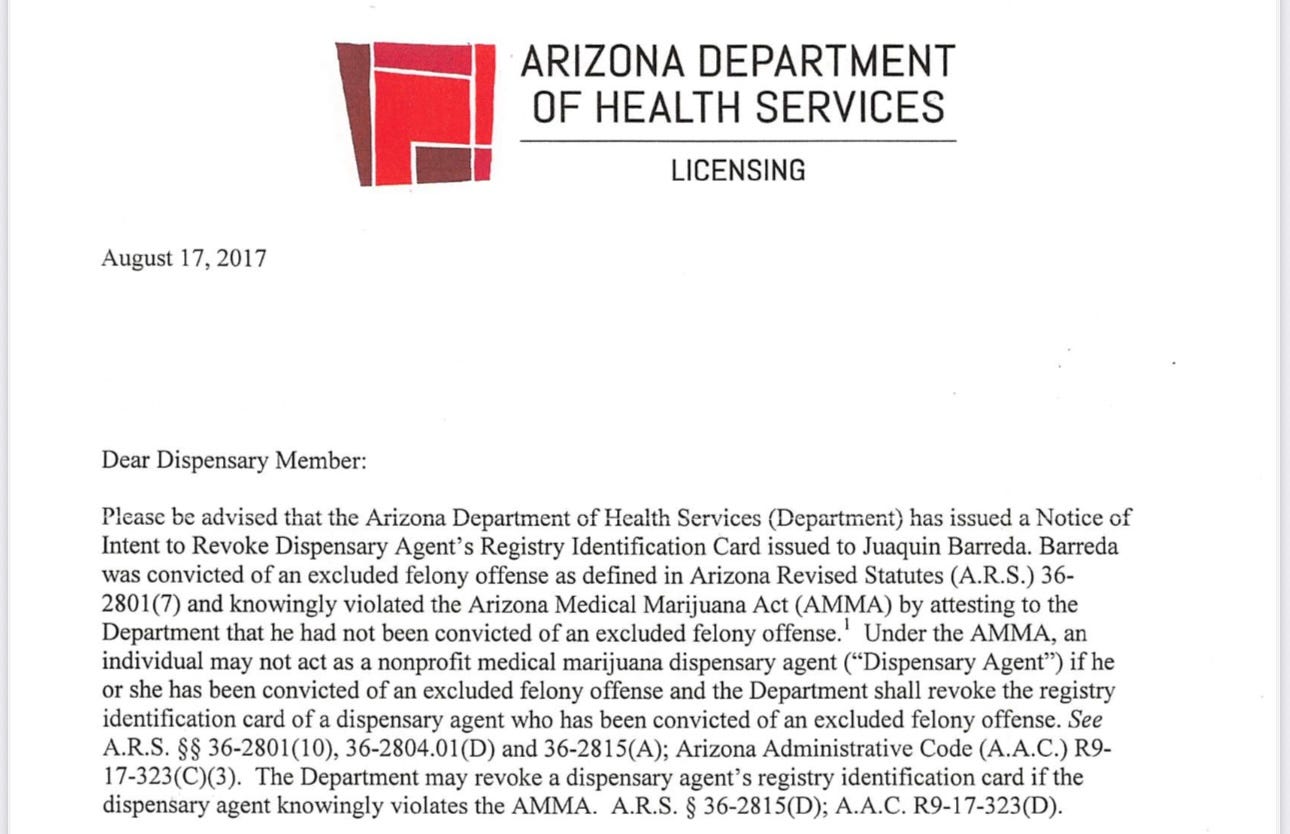

The Case Of Joaquin “Jack” Barreda

The story of Jack Barreda underscores the sharp disparity in how Arizona’s cannabis laws have been enforced—especially against those who are young, poor, and powerless.

In 2017, the Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) revoked Barreda’s dispensary agent license after uncovering a 2015 felony drug conviction. Unlike a principal officer or license owner, a dispensary agent is simply a worker behind the counter. Yet the state treated his youthful mistake as grounds for permanent exclusion.

At age 20, Barreda was convicted in Pima County Superior Court of Unlawful Possession of a Narcotic Drug, a Class 6 undesignated felony. He received 18 months of probation, which ended in 2016. With only a public defender and little understanding of the long-term consequences of a plea, he thought he was doing the smart thing. Instead, he locked himself out of an entire industry.

When Barreda applied for dispensary agent cards in 2016 and 2017, he attested that he had no felony disqualifications. ADHS later determined those attestations were false, and in August 2017 issued a Notice of Intent to Revoke his card. State law required it: the Arizona Medical Marijuana Act barred anyone with a felony drug conviction from serving as a dispensary agent.

At the time, Arizona law offered no path to expungement. It wasn’t until voters passed Proposition 207 in 2020 that limited expungement became available—and even then, it covered only narrow categories of marijuana-related crimes: small possession, cultivation of up to six plants, and paraphernalia. Barreda’s conviction, classified as a narcotic drug, didn’t qualify. He maintains it was actually a concentrated cannabis product, but because of how the state classified it, harsher penalties applied and the expungement law never touched his case.

The ultimate injury is that his conviction began as a Class 6 undesignated felony, which could have been left open to reduce to a misdemeanor after probation—had he had a savvy attorney. Instead, it was designated as a felony, permanently closing the door on his participation in Arizona’s cannabis program.

Contrast that with Michael Halow. In 2004, Halow pleaded guilty to aggravated assault in Texas, and as part of the deal, multiple 2003 charges—including counts of sexual assault of a child and producing child pornography were dismissed. After completing community supervision, his remaining charges were also dismissed.

Despite having a record, Halow later inserted himself into Arizona’s social equity licensing program, gained control of at least five winning licenses, and now promotes himself as a multi-state cannabis entrepreneur.

The contrast is stark: Barreda, a low-level worker, was permanently barred for a probation-level cannabis conviction that couldn’t be expunged. Halow, with resources, connections, and skilled counsel, walked away from far more serious charges and still managed to embed himself in Arizona’s cannabis market.

This is what unequal enforcement looks like. Small players are punished to the fullest extent of the law, often with no chance to recover, while politically connected operators and corporate-backed actors maneuver through loopholes in so-called “equity” programs.

The result is a two-tier system: rigid rules for individuals, exceptions for the powerful.

Here’s our conversation with Jack: